VUCA – Uncertainty and the Challenges of Strategizing

Written by Kent Thorén

Executives and strategists are paying increasing attention to the concept of VUCA, which stands for Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity. Indeed, those are key challenges when taking decisions and making strategies, but perhaps not in the way most people think. As actions under VUCA are much more effective if these challenges are taken into account, both individually and in interaction, some deeper discussion appears worthwhile.

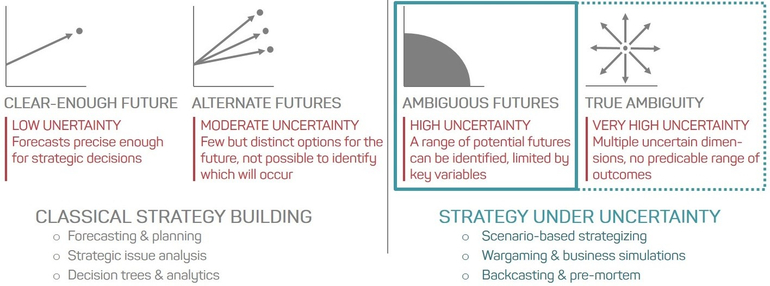

In management and strategy science, uncertainty is usually defined simply as a lack of information. In other words, it is anything short of certainty, or knowing for sure. In principle, decisions always involve uncertainty as all decisions are about the future and all certain facts are about the past. For example, when we deal with new things that we never encountered before, uncertainty occurs when we cannot determine all aspects of the work lying ahead (often called “task uncertainty”). In a brilliant HBR article Courtney and colleagues refine uncertainty on a four-level scale indicating “true ambiguity” as the most difficult circumstance.

Image inspired by Corteney et al., 1997.

But it is also possible to think of ambiguity as different than just lack of information. It concerns the equivocality of situations and difficulty to understand cause-effect relationships. So there may be plenty of information but it is not usable, as there not enough contextual understanding to apply it. In contrast to absences of information, which can be resolved by getting questions answered, ambiguity involves so much multiple and conflicting interpretations, that discussion and sense-making is needed to even start figuring out which questions to ask.

Complexity and volatility, on the other hand, belong to a somewhat different category of challenges. They are attributes of the actual objective situation, rather than of the availability and quality of information about it. Complexity can be seen as the number of variables in an “information set” relevant for a certain decision, but also includes the amount of interaction between those variables. Volatility can then be regarded as the rate of change within the information set. Both of these attributes drive uncertainty (in terms of ignorance about the value for a variable) and ambiguity (in terms of ignorance of whether a variable exists in the set at all).

Dealing with VUCA

If possible, it is useful to decrease uncertainty to reduce risks and improve the quality of decisions. This requires information. But, moving downwards through the four levels of uncertainty requires information of different kinds. Ambiguity needs to be resolved first, and this is only done with “rich information”. Clarifying, context defining, and sense-giving rich information requires reasoning and one of the most effective methods is discussion that are genuinely open so opinions get exchanged, questions can be spoken, and problems get co-defined. This process frames the need for additional information step by step. Discussions, it seems, have the interesting power to transform ambiguity into residual uncertainty.

The type of information that reduce ambiguity will however not be useful for resolving lower level uncertainty. Instead, uncertainty on lower levels (in particular level 1 and 2) is cured by so-called “lean information”. Lean informaiton is concrete and more factual in nature. It is the result of specific decisions or fact finding rather than of co-constructed understanding. For example, defining a plan benefits from concrete knowledge about time frames and budget constraints. These are very lean pieces of information that can be condensed to numbers with no need for interpreting discussions.

These principles of gathering and applying information should be the first choice when faced with VUCA. Only after that it makes sense to go into more costly options proposed by some researchers*. For example, volatility can be met by stockpiling of resources, thus giving preparedness by maintaining slack, and ambiguity can be reduced by engaging in trial and error experiments. Investing in such activities can be very useful for further reduction of risks and who knows, they may uncover unexpected opportunities as well!

Vision as a substitute for certainty

In VUCA situations there will always be areas where critical information is unavailable despite efforts to discuss and find thing out. Therefore, strategist also need other means to support their decisions, like modelling, simulations, hedging, or monitoring trends. Still, when you take a decision (in contrast to making a conclusion) it will always to some extent involve a “leap” over uncertainty. There is a point where investing in further analysis is unlikely to pay off in better decisions and research suggest that it is much longer from paralysis-by-analysis than we may think.

This leads us to a more philosophical aspect about strategic management: Managers will have to accept that comprehensive certainty about the future is not feasible. But it may also not be necessary. It is, after all, intentions that drive action, not facts. Intentions are formed primarily on our belief about which ends that are worth pursuing and which means that will be effective, while facts mostly play the role of weeding out the least promising courses of action. Strategy researcher Igor Ansoff famously suggested that this is the core purpose of strategizing; to provide organizations with intentions so they can function rationally. Leadership is decision-taking, not conclusion-making.

Inspiration:

Ansoff, H. I. (1991), “Critique of Henry Mintzberg’s ‘The design school: reconsidering the basic premises of strategic management”, Strategic management journal, Vol. 12, No. 6, pp. 449-461.

* Bennett, Nathan, and James G Lemoine (2014), “What a Difference a Word Makes: Understanding Threats to Performance in a VUCA World.” Business Horizons, 57: 311–17.

Bennet, N. and Lemoine, J. G. (2014), “What VUCA Really Means for You”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 92 No. 1.

Courtney, H. G., Kirkland, J. and Viguerie, S. P. (1997), “Strategy Under Uncertainty”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 75 No. 6, pp. 67-79.

Daft, R. L. and Lengel, R. H. (1986), “Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design”, Management science, Vol. 32 No. 5, pp. 554-571.

Hedberg, B., and Jönsson, S. (1977), “Strategy formulation as a discontinuous process”, International Studies of Management & Organization”, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 88-109.

(There is also a leadership paradigm called “VUCA Prime” that is proposed to be effective. It uses the same acronym for prescribing leadership tactics for VUCA environments, e.g. Volatility is met by Vision etc. However, considering the nature of the different VUCA dimensions, VUCA Prime appears to make very little sense.)

This article was originally published on LinkedIn.